by Dr. Craig Dahlgren, Executive Director at PIMS

On April 13th, the Perry Institute for Marine Science hosted its first webinar on Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease. In case you missed it, watch the full recording below:

The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally changed the way we live our lives, but humans are not the only species vulnerable to rapidly spreading diseases. The newly emergent Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD) poses what may be the greatest threat (along with climate change) to Caribbean reefs.

SCTLD was first discovered off of Miami’s coast in 2014. Since then, it has spread throughout Florida’s reefs, where many corals are so threatened that the state has begun to go to such extreme measures as transporting healthy corals from the reef to safe locations at public aquaria throughout the US. This “Noah’s ark” approach aims to save species and preserve a minimal level of genetic diversity. However, Florida is not the only place affected.

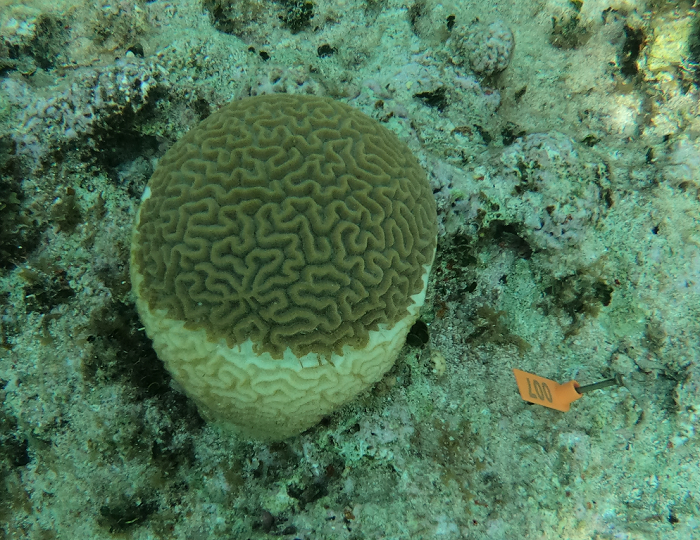

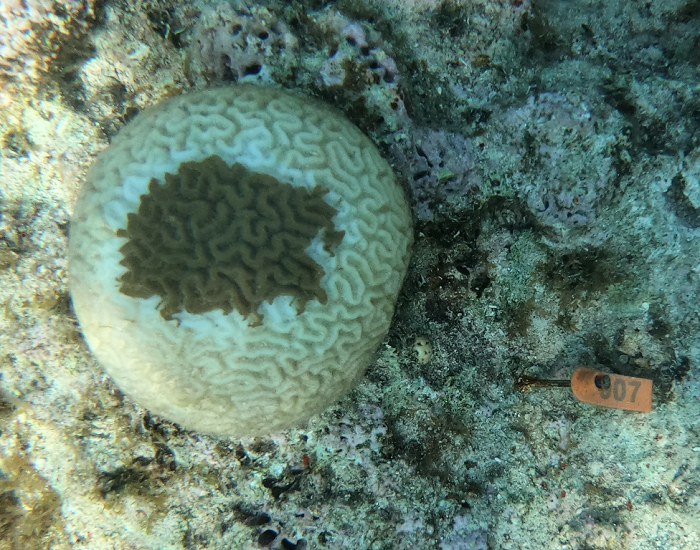

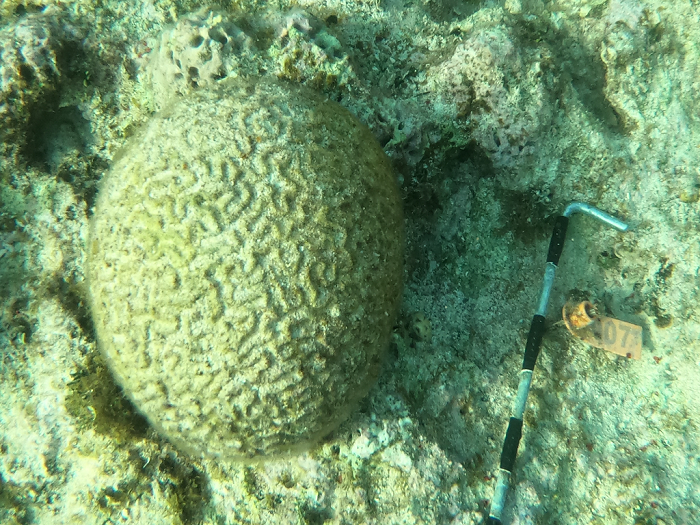

Over the past 2-3 years, SCTLD has spread across the northern part of the Caribbean from Mexico and Belize to Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Turks and Caicos, The Virgin Islands, Saint Martin and Saint Eustacius. Over the past few months, we also found our first confirmed cases in The Bahamas off the coast of Grand Bahama. Earlier in March, PIMS led a team comprised of representatives from the Bahamas National Trust, Coral Vita and the Grand Bahama Port Authority. We assessed 25 reefs along over 40 miles of the southern shoreline of Grand Bahama at depths of 6-50 feet.

We found evidence of SCTLD across all sites, with 18 species of corals infected, and upwards of 90% of corals infected or dead for some species in some locations.

Data suggests that the disease epicenter in Grand Bahama is either in the port area or around the Port Lucaya area, suggesting introduction through vessels via bilge water or ballast water, rather than natural currents. With that being said, the spread of the disease has been rapid. SCTLD has expanded to much of the southern shoreline of Grand Bahama over a period of just 6-8 months. Its rapid spread in Grand Bahama is likely due to a combination of natural ocean currents in the area, increased spread during Hurricane Dorian, and unintentionally even spread through human activity such as fishing and diving. The latter is because diving and fishing activity causes bilge water and gear contamination at a site where the disease is present, which causes it to move to an uninfected site.

SCTLD is a rapidly spreading epidemic like COVID-19, but one that is even more devastating to our reefs in a myriad of ways.

We know that COVID-19 is about twice as contagious as the flu and kills about 1-2% of those infected at present. By comparison, SCTLD doesn’t just infect one species. The disease can infect over 20 different species, which is about half of the reef building coral species found in The Bahamas. Furthermore, in Florida, SCTLD killed 30-95% of some species of corals at monitoring sites over a 2-3 year period.

To make matters worse, scientists have yet to determine what the exact pathogen(s) are that are causing this disease. It appears to be caused—at least in part—by bacteria. SCLTD can be spread through the water without requiring direct contact between corals or transmission by fish or other animals that move about the reef.

While not a risk to human health, SCTLD can have a similar impact to COVID-19 on the economy of The Bahamas and other places where it has spread through its effect on coral reef ecosystem function. SCTLD infects and kills some of the most important reef building corals, and poses the risk of negatively altering the balance of coral reef ecosystems. It therefore compromises the ecosystem services they provide, including fisheries, dive tourism and coastal protection of beaches and infrastructure.

The Perry Institute for Marine Science is currently working with government agencies in The Bahamas and international partners to develop strategies to prevent the spread of this disease. Like COVID-19, we don’t have a cure or vaccine for the disease, so we must work on slowing or preventing its spread. Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease is a waterborne disease, so we cannot prevent its spread in water currents.

So, what can we do to stop the spread of SCTLD and protect our reefs?

- Limit how the disease is transported by humans by disinfecting bilge water and dive/snorkel gear between dive sites using a mild bleach solution of hydrogen peroxide-based disinfectant.

- Commercial ships must properly exchange ballast water by to prevent spreading the disease.

- Report new locations where corals are showing signs of the disease. If we catch it early on a reef, we can prevent its spread to other corals on the reef.