Written by Lily Haines, Communications Director, Perry Institute for Marine Science

Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD) is a highly contagious and lethal disease sweeping through the Caribbean, leaving thousands of dead corals and non-functioning reefs in its wake. The disease, which first surfaced off of Miami in 2014, has spread to over twenty countries in the Caribbean in less than a decade, creating a full-fledge pandemic. Sadly, it’s already killed some of the world’s oldest and largest reef-building corals in the region.

SCTLD was first identified in The Bahamas in December 2019, on reefs directly adjacent to a shipping port in Grand Bahama. Researchers at the Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS) attribute the initial outbreak of SCTLD in The Bahamas to commercial shipping vessels that take on and expel large amounts of water as they travel from place to place. This ballast water can quickly spread invasive plants, animals and waterborne disease like SCTLD from one part of the ocean to another. Since its arrival to popsicle-blue waters of The Bahamas, SCTLD has spread to six other islands and has been reported, but unconfirmed, in even more. Spread between islands of The Bahamas is likely due to local currents and smaller boat travel.

How to identify SCTLD on the water

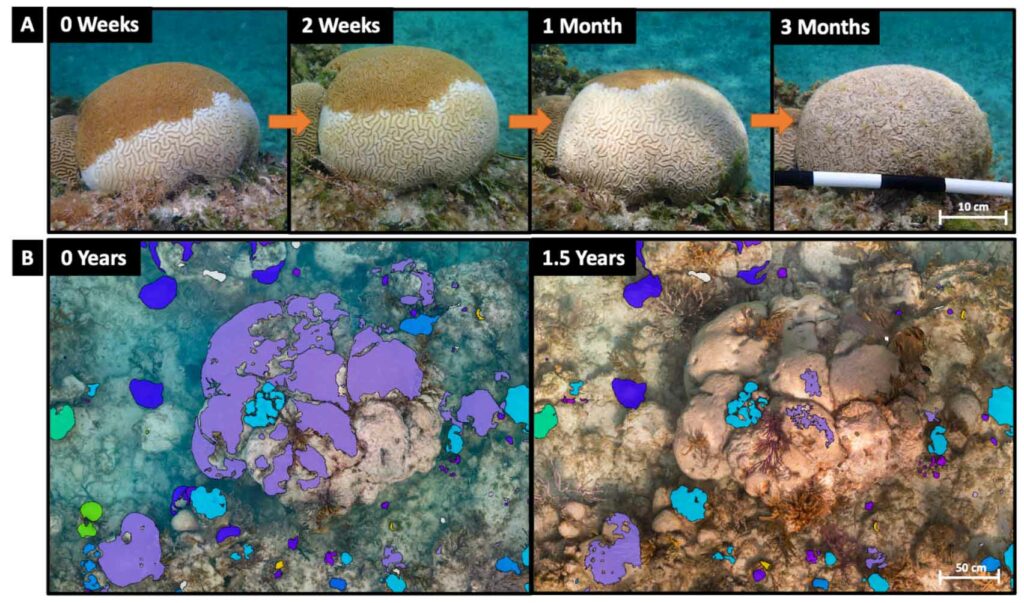

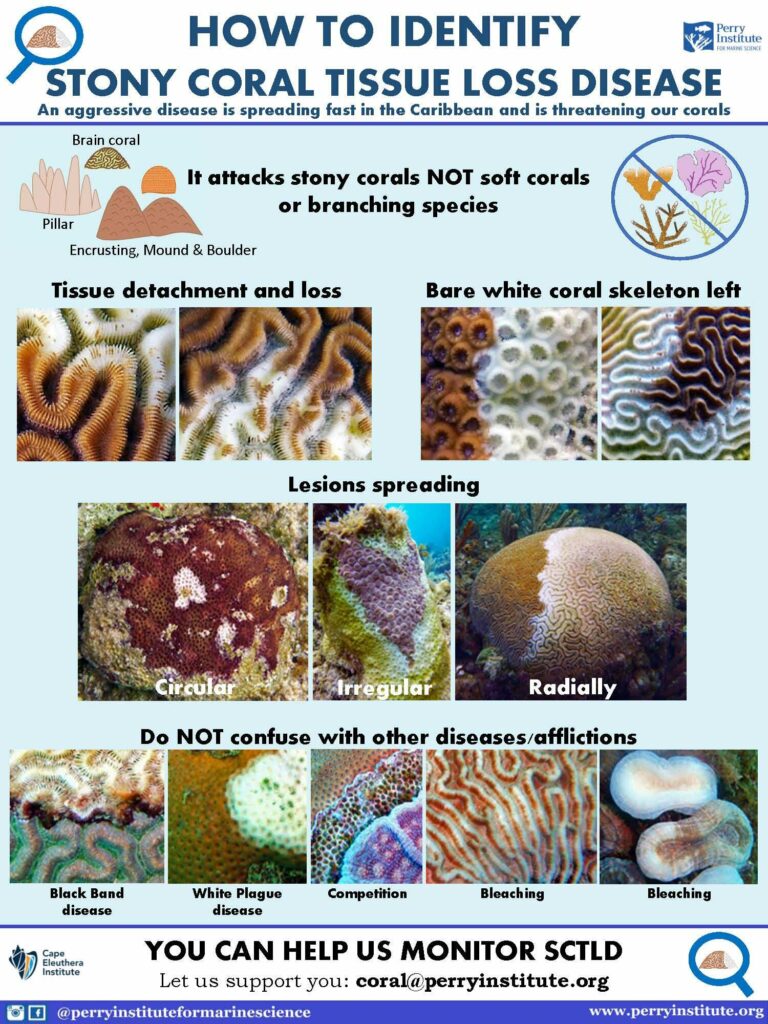

All boaters, divers, fishermen and ocean-lovers have a hand in stopping the spread of SCTLD. One of the most telltale signs of SCTLD is the presence of bone white coral skeleton directly adjacent to healthy, colored tissue. Bone white skeleton signifies an extremely rapid and recent death of previously healthy coral tissue, likely having occurred within the last couple of days. The presence of both living and recently dead tissue reveals an active infection, and lesions may spread radially, irregularly, or as multiple blotches within the same colony. After about a week, turf algae will begin to colonize the bone white skeleton, covering it with a brown-green hue.

A couple of other diseases and massive bleaching events have affected Caribbean corals in recent years, but none have been as contagious or lethal as SCTLD. It is important when to not confuse other diseases, predation, or bleaching with SCTLD. When it doubt, take a picture of the suspected disease coral so you can refer back to it later when you report sightings of the disease (see next section).

Become a citizen scientist: report corals infected with SCTLD to the Perry Institute

If you ever go swimming, fishing, scuba diving or snorkeling in The Bahamas and you see what you think might be SCTLD, snap a couple of pictures and send them to our partner non-profit, the Perry Institute for Marine Science. Include the coordinates of where you spotted the disease or those of a nearby landmark as well. This helps scientists track the spread of the disease throughout the islands of The Bahamas and will help drive country-wide assessments and treatment plans.

You can report sightings of SCTLD at https://www.perryinstitute.org/sctld or by emailing coral@perryinstitute.org.

Bahamas Coral Gene Bank Equipment Arrives at Atlantis Resort

We are thrilled to announce that The Bahamas Coral Gene Bank at Atlantis, Paradise Island has received two 40-foot containers packed with essential lab equipment

Marine Mammal Mysteries: Stranding Response Efforts in The Bahamas

Recent Strandings in The Bahamas Sperm Whale, Eleuthera, December 2023 In December 2023, the head of a sperm whale washed ashore at Lighthouse Point in Eleuthera.

Reef Rescue Network: Growing Stronger

The Atlantis Blue Project Foundation is thrilled to share inspiring news from the frontlines of marine conservation. The Reef Rescue Network’s “Coral is Calling” campaign,

Coral Is Calling: A New Wave of Marine Conservation and Sustainable Tourism in The Bahamas

We are thrilled to announce the launch of the “Coral is Calling” campaign, a pioneering nation-wide initiative aimed at bolstering coral reef restoration and sustainable

2023 Bleaching Crisis in The Bahamas

The breathtaking coral reefs of The Bahamas, renowned around the world for their vibrancy and diverse marine life, are under serious and immediate threat as

Saving The Blue: Studying the Critically Endangered Smalltooth Sawfish

Hello, fellow marine enthusiasts, Scientist and Conservationists! My name is Khrys Carroll, and I am from Central Andros, The Bahamas. I am a marine scientist